I’ve been working on a project that involves measuring the location of an object in the sky using a mobile phone. The idea is to point the camera on the back of a phone at an object and get a measurement of where the object is.

Altitude Azimuth

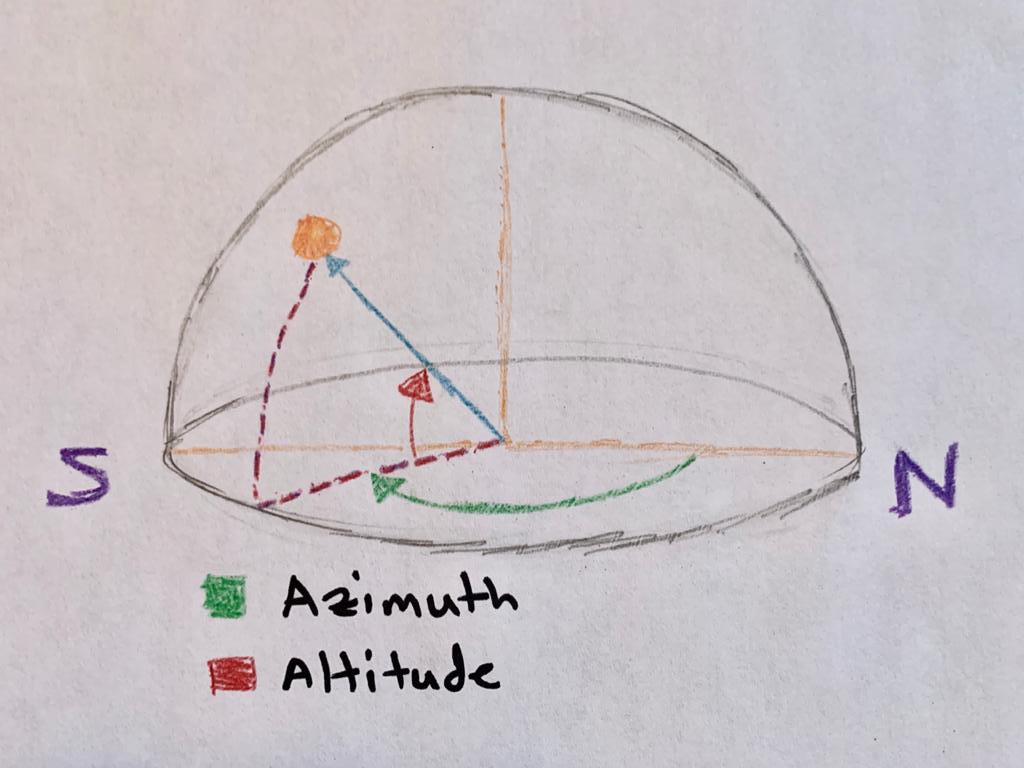

A common way to describe the location of an object (eg stars) in the sky are Azimuth and Altitude measurements. Azimuth is just how far around the compass (from north) you are facing. And altitude is how far up the sky from the horizon you are looking. So an object to the east would have an Azimuth of 90°. If it is halfway between the horizon and directly above you, the altitude would be 45°. The goal was to hold up my phone and know the Azimuth and Altitude that the phone camera (on the back of the phone) is pointing. We could have required that the user hold the phone up vertically or horizontal, but doing it perfectly would be hard. Instead we don’t care if the phone is vertical, horizontal, or diagonal. The user could even spin the phone screen, but as long as a certain object in the sky stays centered in the camera view, the Azimuth and Altitude should remain the same.

Device Orientation

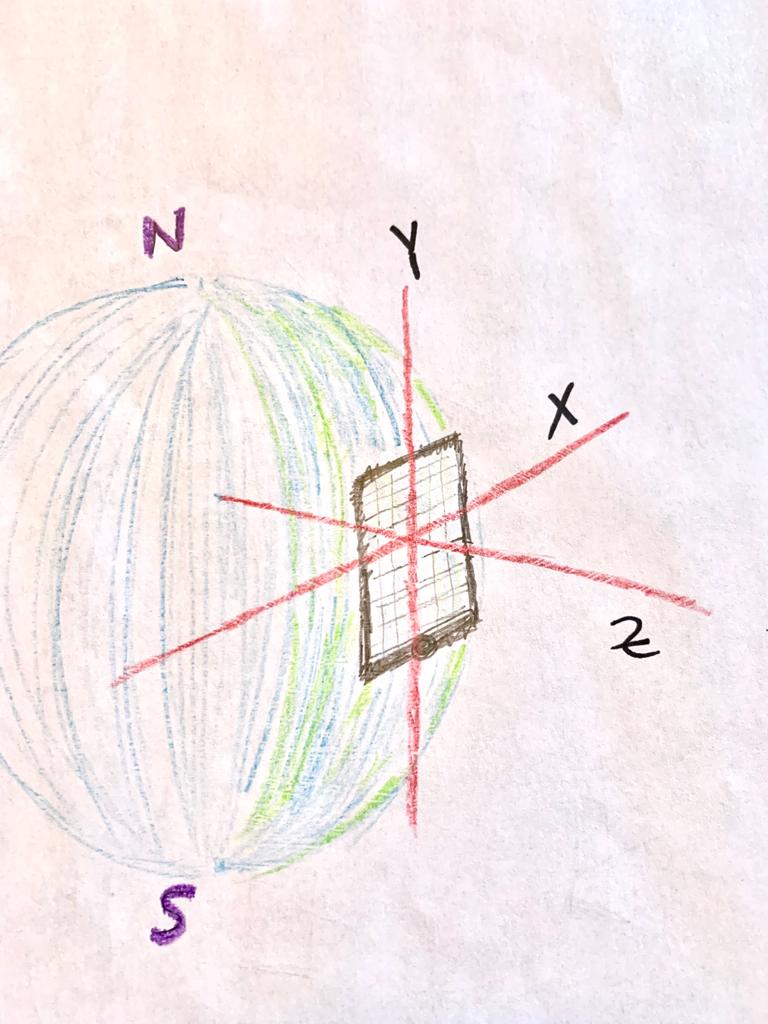

Mobile devices have a number of sensors that can be used to describe how they are oriented. The AbsoluteOrientationSensor is in browser’s javacript API and can tell you in 3 dimensions which way the phone is oriented, relative to magnetic north. More specifically it tells you how the phone is oriented relative to the “default position”. Where the default position is lying the phone down flat with the screen facing up, the top of the phone to the north, and the right side of the phone (when facing the screen) to the east. To tell you the current orientation of the phone, the sensors describes how the phone needed to be rotated to go from its default position to its current position.

Quaternions to describe rotations

Rotations in 3d are often described using quaternions, that is also the case for the AbsoluteOrientationSensor interface. A quaternion is simply a list of 4 numbers. Really understanding quaternions is quite difficult, but it suffices to understand that they describe a way to rotate an object in 3d from one orientation to another.

Quaternion to 3d Vector

So the data coming from the sensor describes how to rotate the phone from the default orientation to the current orientation. And we want to convert this into Altitude and Azimuth.

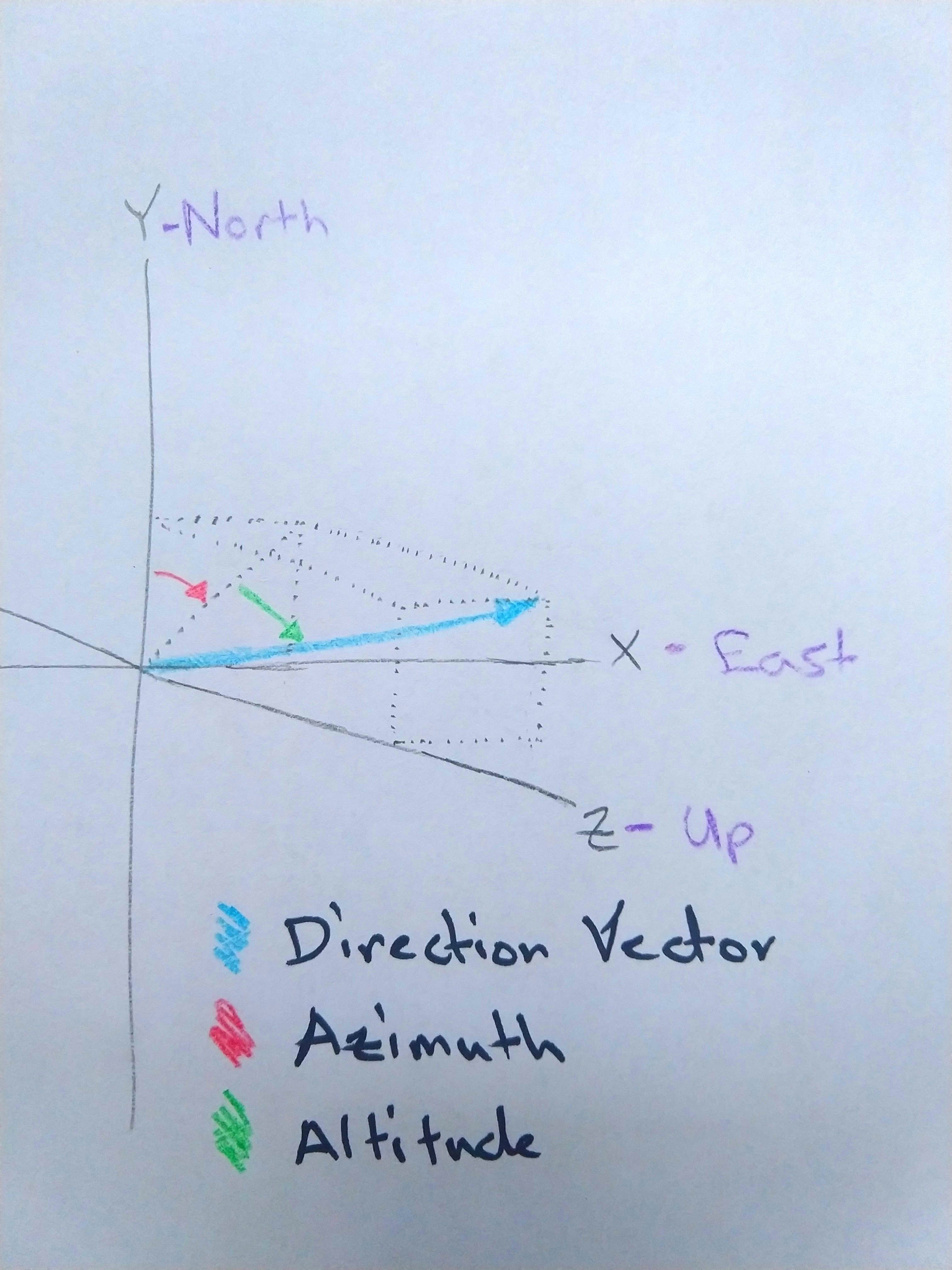

We’ll start by simplifying how we talk about the phone orientation. Since we really just care about which way the phone camera is pointing, we’ll call this the phone direction instead of orientation. We don’t care about the screen orientation

A good way to describe directions in 3d is a 3d vector. So we want a vector for the direction the camera is currently pointing:

The quaternion describes how to rotate the phone from the default orientation to the current orientation, but it really can be used to rotate anything. For example it could be used to rotate a vector describing which way the camera points when the phone is in the default orientation. What would such a vector look like? Well it’s just a vector that points straight down. So the X and Y values need to be 0 and the Z values needs to be negative. Such as [0, 0, -1]. Let’s call this vector the default direction vector. If we rotate it by the sensor’s quaternion, the result is the current direction vector.

One cool thing about using 3d vectors to describe the phone direction, is that we lose information about the screen orientation (which we don’t care about). It just gets dropped off during the rotation. This was the main stumbling block for me in figuring out how to do this conversion.

3d Vector to Azimuth/Altitude

Recall that 2d vectors and points can be described using cartesian coordinate or polar coordinate. Meaning an angle and a distance. Well 3d vectors can be described in a similar notation called spherical coordinates. They are just 2 angles and a distance. And the Altitude and Azimuth are just the two angles of Spherical coordinates, they don’t require a distance since they just describe a direction.

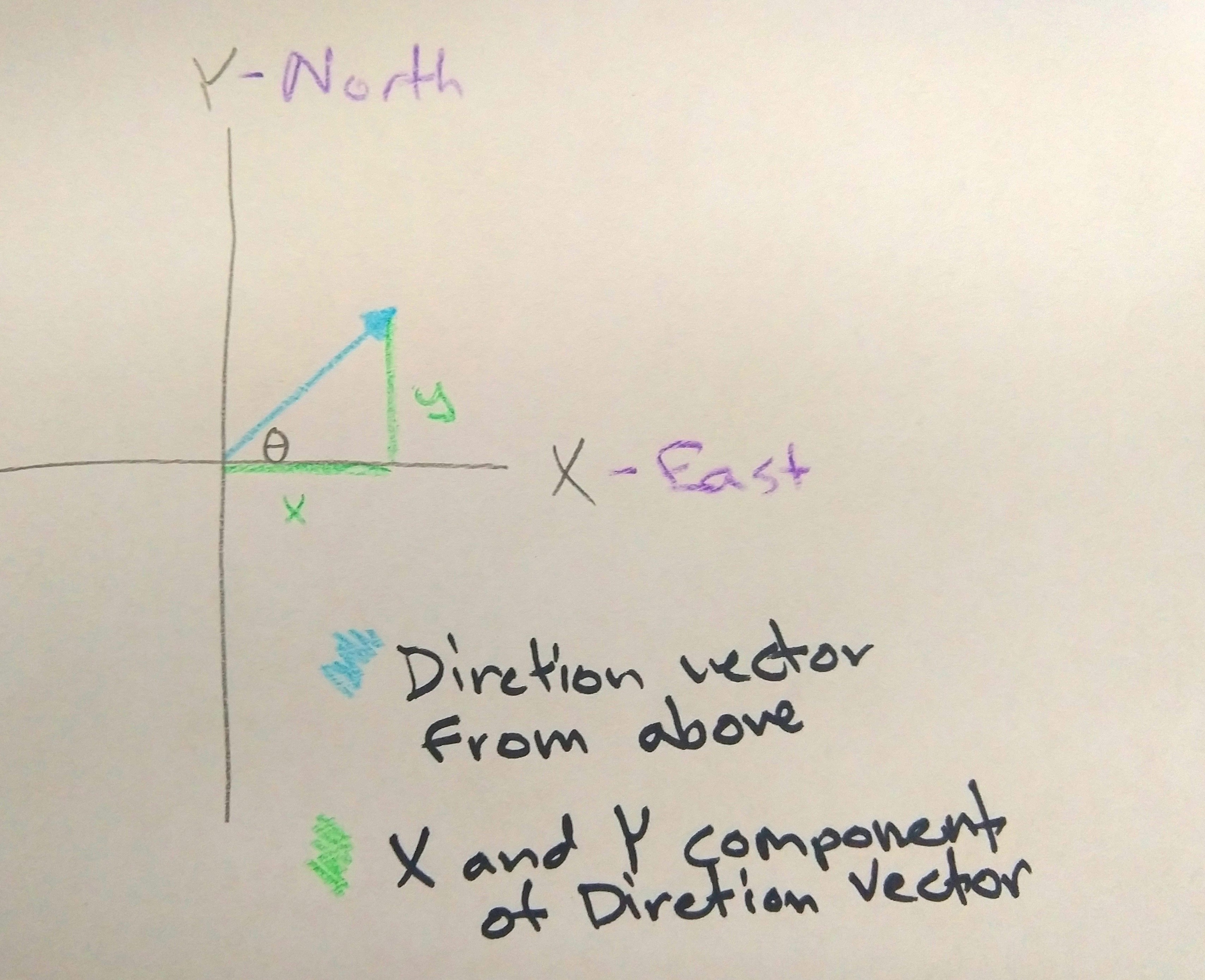

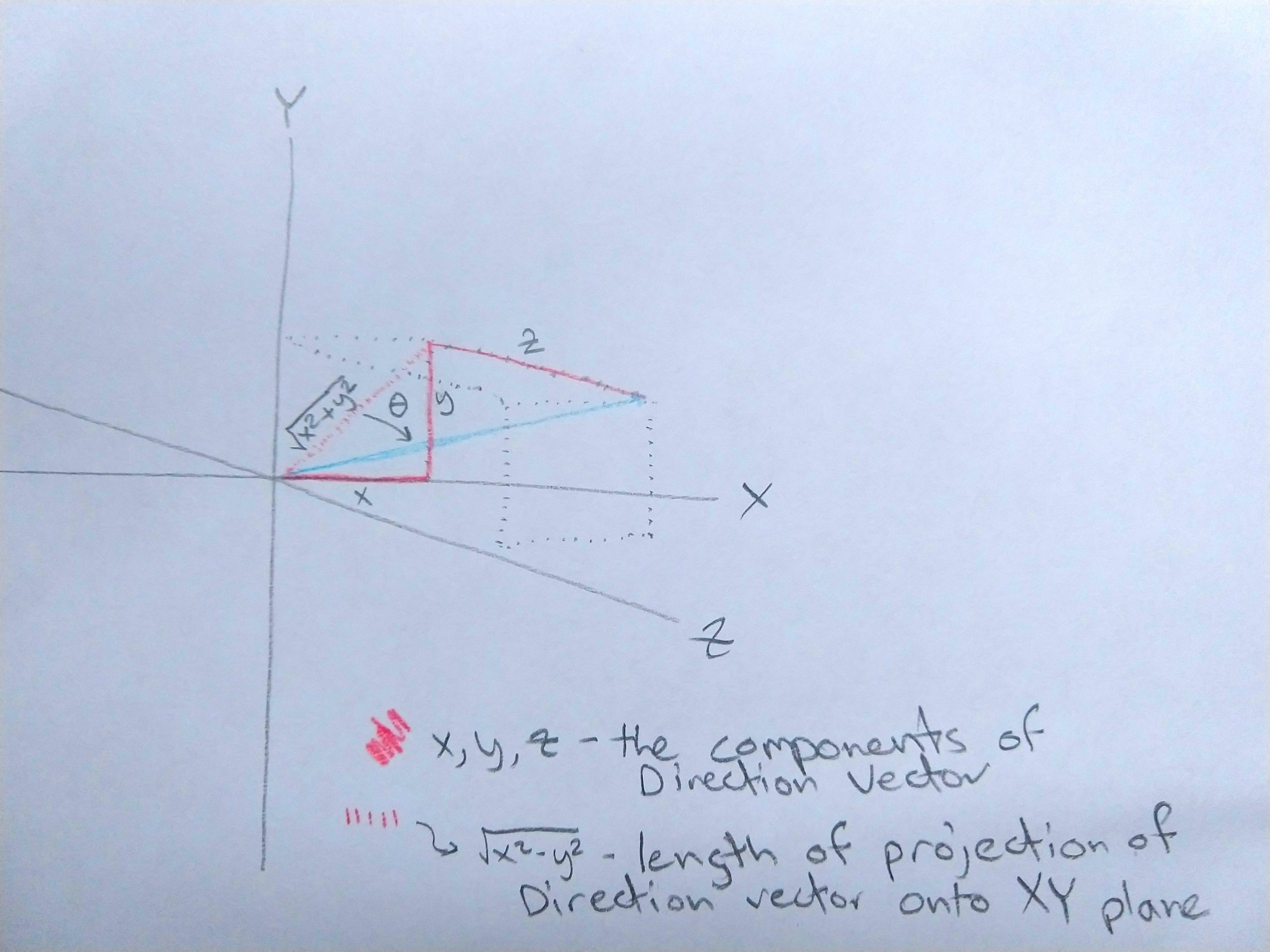

First we’ll find Azimuth. Look at the current direction vector from above:

We know that \(\tan(\theta) = \dfrac{y}{x}\) , or \(\theta = \arctan(\dfrac{y}{x})\)

We’ll use the arctan2 function which takes into account the signs of both y and x, so it provides a \(\theta\) for all the way around the circle. The \(\theta\) we have here has a few problems. It’s values is between \(\pi\) and \(-\pi\), it goes in the wrong direction (half clockwise, half counter-clockwise), and starts at the wrong spot (East rather than North). It requires some massaging to get in the right form ([0, \(2\pi\)] clockwise from North), but that’s pretty simple, I’ll leave it as an exercise for the reader. So, we have succesfully found the azimuth.

Now let’s find the Altitude. Similar to Azimuth we’ll need the two non-hypotenuse sides of a right triangle to get the angle. One side will be Z component of the vector. But the other part of the triangle is a combination of the X and Y components. Use the ol’ pythagorean theorem to find the length of the bottom arm of the triangle. That value is \(\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}\) so this time \(\theta = \arctan(\dfrac{z}{\sqrt{x^2 + y^2}})\) And thats’ the altitude.

Conclusion

Just to wrap up, let’s go back over what we’ve done. We took the orientation of a phone, in the form of a quaterion descibing how the phone is rotated relative to being flat on the ground with top to the North. Then we produced a 3d vector describing the direction that the phone is pointed, throwing away the information about the screen orientation. Then, throwing away the vector’s length, we converted it into two angles: the Altitude and Azimuth.